Holocracys – the Future of Work

Work is changing. When Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh announced in March that the company would adopt Holacracy, it was clear that the alternative organizational structure, famous for its lack of managers, was becoming more mainstream. Holacracy has been adopted by other companies around the world, including the publishing platform Medium and productivity consultants the David Allen Company. But where did this radical new idea come from?

Philadelphia-based entrepreneur Brian J. Robertson was looking for a better way to organize his software company when he came up with what would eventually become Holacracy. The new organizational system forgoes the traditional top-heavy management structure in favor of something much flatter: Authority is distributed across the company instead of being concentrated at the top of the org chart. But wait—No bosses? Is this guy for real? We sat down with Robertson to learn more about the ins and outs of Holacracy.

How the hell did this guy from Philly hatch an idea that’s infiltrating companies in Silicon Valley?

Robertson: Yeah, I know isn’t that weird? It’s actually around the world. We’ve got two departments in giant international companies in Europe. There’s a big company in Australia. It’s global now. Yeah, that’s a good question. I wonder that myself sometimes.

When I started doing this in my software company, I wasn’t trying to change any other business. I just wanted a better way to run my company. What drove me was just the sense that there’s got to be a better way to work together, to organize, to run a company. I felt so many limits of the companies I had been in before.

Somewhere along the line I met some people. One was a guy at a conference that became my cofounder of HolacracyOne, Tom Thomison. He was another entrepreneur. I invited him in just to see what I was doing. And he was like, “This is really cool. This is really different.” And then the Wall Street Journal did an article on a really early version in Holacracy’s experimentation. And that was kind of a wake-up call too of like maybe the rest of the world does care. So I just started exploring. I started blogging more and it just started spreading virally.

What I’ve found Is people are hungry for better ways to organize. I was on CBS This Morning a couple weeks ago, and it had 3 million viewers. We’re tapping in to something that people were already sensing and hungry for, which is a better way to run a company.

What I’ve found Is people are hungry for better ways to organize. I was on CBS This Morning a couple weeks ago, and it had 3 million viewers. We’re tapping in to something that people were already sensing and hungry for, which is a better way to run a company.

Look at the world around us: Our whole economy has shifted to a totally different paradigm than the top-down directed economies of the past. And then we go into companies and it’s like a throwback to a thousand years ago and a feudal empire.

The management hierarchy was fine for the world a hundred years ago. Look at the number of inbound messages people get in a day compared to an executive 50 years ago. They get a few things in their in basket every day from the mail. Fifteen years ago it was just the email. Now it’s tweets, and it’s social media traffic and it’s massive amounts of in-bounds. We need more responsive organizational designs.

What is this, office anarchy? How can this possibly work? What, in your view, are the biggest misconceptions about Holacracy?

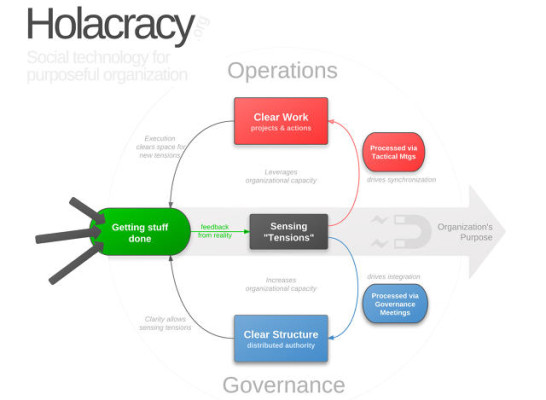

I think there are two. One is exactly what you said: the idea of when you don’t have a management hierarchy, you must have no structure. You must throw out all structure and everybody can do whatever. Ironically, Holacracy has more structure—not less—than a traditional management hierarchy. It’s just a different structure, and it actually adapts to keep pace with what’s needed in the company. So you actually have more clear structure, just with less rigid top-down bureaucracy. So that’s one misconception: that it means “no structure.”

The other is that if you have no management hierarchy, it must be that all decisions are made by consensus and that everybody has a voice in everything. And that’s actually not true at all with Holacracy. It’s distributed autocracy. So, any given decision is usually made by one person. It’s just a different person for different decisions, and it’s not broken down into a management hierarchy.

At my company, we do trainings. If we’re talking about what hotel we do our trainings at, that’s not a big group decision. One person makes that decision. They know that they have the power to do that, and everyone knows that they can expect them to not only do that but to do some research around it, and there’s a series of expectations that go with the authority. The same is true for any decision, there just isn’t a manager that can trump that person’s decision and say, “No, don’t do that. Do something else.” But it’s not consensus.

How does that responsibility get assigned? Under Holacracy, how would you designate that person?

The first thing is: Let’s just identify that we need somebody to do that function. And in this way, Holacracy really focuses on organizing around the needs of the work, as opposed to a management hierarchy, which is often more organizing people in kind or power relationships with other people. It’s more like a feudal system of who’s going to be the lords, the barons, the peasants. Holacracy is, first and foremost, about forgetting about the people and the personal politics. Let’s organize the work.

So, we’re going to do trainings. We need a function to choose hotels and structure logistics. Okay, let’s create a role for that. There’s a governance meeting where somebody identifies that we need to do trainings. We need somebody that’s choosing venues for trainings, so let’s create a role that has the authority to do that and we’ll give them some expectations. Then we need another role that’s going to establish price points for the trainings. Let’s create a role that owns the business model of the trainings and defines price points and approves cost budgets or whatever else, and give that role that authority. All that happens in the governance process.

So, we’re going to do trainings. We need a function to choose hotels and structure logistics. Okay, let’s create a role for that. There’s a governance meeting where somebody identifies that we need to do trainings. We need somebody that’s choosing venues for trainings, so let’s create a role that has the authority to do that and we’ll give them some expectations. Then we need another role that’s going to establish price points for the trainings. Let’s create a role that owns the business model of the trainings and defines price points and approves cost budgets or whatever else, and give that role that authority. All that happens in the governance process.

The interesting thing to note is we don’t make the specific decisions in the governance meetings. We’re kind of defining the pattern of how we work. We’re not deciding to use the Hilton or whatever. We’re just saying that we need a role to make that decision, and it needs the power to do it, and it needs some responsibilities along with it. It needs to maybe integrate the needs of the trainer and the room setup and whatever else.

Operationally, when it comes time to execute, that designated person then needs to go make the decision. So we identify the needs of the role in this collaborative governance process, but we don’t actually execute that way. For execution, some other role has the function of finding people to fill roles. Some other role says, “You’re a really good fit, I know you do a lot of logistics. So will you do our venue coordinator role?” And you say, “Sure.” That gives you the power of that role, and then you get to go do some research and make the decision on what venue to use. You might get input into that, but you know it’s your authority to decide.

It ends up working more like a society in that we have property boundaries. I don’t come to consensus with my neighbors when I want to decorate my house. I know it’s my house and I know I have full autonomy to lead my house. I do have some agreements with my neighbors. And then they have their property and I know not to go take their car without their permission, right? It’s kind of the same.

The governance process breaks up the property lines and says you’re going to control the hotels, you’re going to control the business model, the trainer is going to control the slides and the content of the training. We have three roles there, each with their territory, and each with connections and expectations. The trainer can expect that you’re going to integrate their design of the meeting-room space in choosing a venue. Business-model guy can expect that you’re not going to go over the budget that he allows for the venue or whatever else.

The governance process breaks up the property lines and says you’re going to control the hotels, you’re going to control the business model, the trainer is going to control the slides and the content of the training. We have three roles there, each with their territory, and each with connections and expectations. The trainer can expect that you’re going to integrate their design of the meeting-room space in choosing a venue. Business-model guy can expect that you’re not going to go over the budget that he allows for the venue or whatever else.

You mentioned the need for Holacracy to be adaptable. How would the organization adapt if, say, somebody wasn’t a fit for the role they wound up with?

Sometimes you do need to reassign a role, and there is another role that can do that. Another misconception is that in this structure, people are just stuck in roles forever, and if they do a bad job, then oh well, everyone ignores it. Which is not true at all. If somebody’s doing a bad job, someone else is probably going to feel like, “Hey, what’s going on there?” But I find 90% of the time, when we feel like somebody’s doing a bad job, it’s just because we have different implicit expectations.

What Holacracy first does is let us get clear on what expectations serve the business. And once we’re clear on them, then if you’re not doing a good job fulfilling clear explicit expectations, then great, somebody else needs to pull you out of that role and put someone else in it. And there’s still somebody that can do that. But the first step is always to get clear on what we really need to expect, because often we wield our implicit expectations that are just not shared by other people.

The governance process is not done just once up front. It’s something we engage in regularly—maybe every month—so we can learn. You might leave, somebody else might come in. We want to encode that learning somehow. So we encode it in the structure, for example, as a new expectation for you to find venues that are easy to get to or to make a map. In any company, there are massive amounts of learnings like that. Sometimes the individuals learn but the organization doesn’t. As soon as that person leaves all the learning goes with them. Or worse, nobody learns and we all feel frustration and next time we push on each other harder. And things just kind of keep happening that way.

Under a traditional management structure, you have a boss who knows your specific role and everything about it. And they’re usually pretty well-positioned to ascertain whether you’re doing a good job or not. With authority and roles spread out, does it become harder for the organization to figure out who sucks at their job?

It’s very similar to any other traditional company. This is a challenge in management hierarchies too, especially when you have people that work under a manager that are off doing all sorts of other stuff. Holacracy doesn’t make it any worse, but it’s still often a challenge. Holacracy helps a little, but it doesn’t solve it just by giving more transparency. There’s more processes, there’s more visibility in what the expectations are. A traditional manager probably doesn’t even know what they should be expecting from some of their people who are not as directly connected to them. At least in Holacracy it’s all spelled out. You know exactly what you should be expecting and you can see more clearly. Is this person dropping expectations, or do people just have different ideas of what we should be doing?

I think the transparency helps. But how do you everknow? That’s never an easy call to make. One of the interesting differences with Holacracy is that somebody can’t jump in and tell the person what to do. They’re bound by the same rules as everyone else. They can request projects and actions, just like anyone else can, but if you’re filling the role, it’s your autonomy to lead it. All that person is doing is saying, “I’ve got someone that’s going to be better at leading the role, and I’m going to make a change.” Which doesn’t necessarily mean firing a person. If you fill roles in other parts of the company, which often happens, you just go spend more time there or find another role somewhere else.

I think the transparency helps. But how do you everknow? That’s never an easy call to make. One of the interesting differences with Holacracy is that somebody can’t jump in and tell the person what to do. They’re bound by the same rules as everyone else. They can request projects and actions, just like anyone else can, but if you’re filling the role, it’s your autonomy to lead it. All that person is doing is saying, “I’ve got someone that’s going to be better at leading the role, and I’m going to make a change.” Which doesn’t necessarily mean firing a person. If you fill roles in other parts of the company, which often happens, you just go spend more time there or find another role somewhere else.

It sounds like people can easily wind up filling several different roles. Without a hierarchy of people overseeing things, how do you keep track who’s doing what?

All of that is spelled out. So you can go in and see all the different roles you fill in all different parts of the organization. We have a software tool called GlassFrog that helps with that. Anyone in the organization can go in and see what everyone else is accountable for. What anyone should be doing. All the expectations and authorities and all of that stuff. So this is our general company circle. And if I click on myself here, I’ll get a list. Here’s all the different roles in our broader company: Applied R&D, engagement lead for our consulting engagements, master coach.

I can see all of the accountabilities in every role I fill. And the purpose of the role—not just the specific activities, but why the role exists. So I can be creative. This isn’t just a job description that nobody looks at because it’s all out of date and theoretical. This is the result of our learning process together. So, these accountabilities are living, breathing, dynamic things, and it’s capturing the teams’ current learning.

If I wanted to assign you to a role in one circle or whatever, I can go look at everything else you’re doing, and make sure that it all kind of lines up. I can have a conversation with you, and you could pull up the list of everything else that’s on your plate so you kind of know how it intersects with other stuff. It’s much more like a marketplace than a typical top-down planned economy. You could fill roles in lots of different circles with lots of different people.

Whose responsibility is it to ensure that that’s up to date? Is it on each person or is that a role?

That’s actually the output of the governance process. No one person is doing it. We come together as a team maybe once a month. We go through a meeting process where anyone that feels like something should change or has some tension that’s not working can bring it up. And then through that process collectively, we’re updating the roles, so it kind of automatically stays up to date. We’re coming together and reflecting on the last month—how did this go, what worked, what didn’t, what do we need to change? It’s then kind of an output of that process. So it’s just inflow you don’t have to ever worry about maintaining.

You started out running a software company, but now you’re running Holacracy One. What do you guys actually do?

Our overall goal is to support Holacracy in the world. We support any company that wants to do something with Holacracy. We then have a whole spectrum of support options ranging from free materials we put on the website, and it scales up from there. We have cheap tools like the book Holacracy: The New Management System for a Rapidly Changing World, which came out last month, and other cheap support programs, and those are more for the do-it-yourselfers, the smaller companies.

We have trainings that we do, which are giving people skills and capacities internally for people to understand the rules, facilitate the unique governance process and all that. And then we do coaching with clients, where we actually come in and we help them launch Holacracy. We’ll facilitate their meetings for many months. I’ll do regular coaching sessions with them as they’re getting up to speed on the whole new paradigm.

It’s kind of like learning to play a new sport. And we’re the coaches. So we come in, for a while we’re kind of doing it with them. We’re leading them through the exercises. They’re doing it and we’re on the sidelines coaching. Then eventually they’re just into it. They get the rules, the plays, the moves, and they’re good to go.

What are the biggest challenges you’ve seen within organizations trying to adopt Holacracy?

The biggest challenges happen after a company decides to do it, and then they have to learn a whole new way to play the game of business. To use that metaphor, it’s like they’re playing one sport. They’re used to it. Everybody internally knows the plays, they know the rules, and then suddenly we’ve thrown out that rule book and we’ve put in a new rule book. And it is literally a new rule book.

One of the hardest things we do as humans is learn new habits, but what’s even harder than that is unlearning current habits. Unlearning a bad habit is really hard, but even harder than that is unlearning a good habit, such as one that worked for you in the management hierarchy. We’ve learned to play the politics, to call the meetings, to build all the buy-in and take all the time to do it and big long meetings, and all this stuff. And those things kind of work as best they can in that system. So they’re good habits in that way. And what Holacracy’s doing is saying, “Okay, get out of your good habits, and instead replace them with even better habits in this new rule set that now is possible.”

In a company going through Holacracy, everyone on the front lines habitually looks up at the boss. You see all eyes turn to the formal boss in the room when a decision comes up. And there’s breaking that habit and replacing it with: If it’s your authority, own it and lead it. It’s your role. You can’t hide behind the boss. The boss can’t bless your decision. There is no boss anymore. You are the boss of your role, so step into it and lead it. And that’s uncomfortable for people.

In a company going through Holacracy, everyone on the front lines habitually looks up at the boss. You see all eyes turn to the formal boss in the room when a decision comes up. And there’s breaking that habit and replacing it with: If it’s your authority, own it and lead it. It’s your role. You can’t hide behind the boss. The boss can’t bless your decision. There is no boss anymore. You are the boss of your role, so step into it and lead it. And that’s uncomfortable for people.

And on the other side, the boss has to let go, right? If the boss habitually jumps in and gives input, which really means direction, on things. Holacracy keeps pushing against that and says to the boss, “You have no authority to tell that person what to do anymore.”

It’s really like the work of an entrepreneur, rather than a manager. It’s not just heroically holding everything and bossing everyone around. The real work of an entrepreneur is building structure so they’re not needed. It’s building the right roles and the right processes, and the right policies so they can get out of it and go create and be creative.

I’ve talked to a lot of entrepreneurs that got frustrated. One of them was Evan Williams, who said when he was growing Twitter, he started as a creative designer and entrepreneur. Then suddenly he ended up as this professional manager and all he’s doing is managing people full time. And he was scared. He almost didn’t want to start another company because he didn’t want to get stuck in that mind-set again. But he knew that if he wanted to be creative on a big scale, he needed to start another company and he was kind of stuck. For him, Holacracy was a way to scale without getting stuck in that heroic, leader, parental, manager kind of paradigm. Instead, he can give everyone else the ability to kind of lead their piece of it and be entrepreneurs together.

A lot of teams are remote these days. How do the principles of Holacracy carry over to virtual teams?

We’re virtual, so it’s something that we’re very used to. A bunch of companies in our network are virtual. I think for virtual companies it’s even more important to have some clear way of organizing, cause it’s even harder to have management hierarchy to work when everybody’s all over the place and the manager doesn’t have direct contact every day with the people they manage. With Holacracy you get more transparency, more asynchronous ways of processing. You get more clarity. You have meeting structures so it’s not coming together on the phone. It’s even harder to have a good meeting than it is in a typical company. Holacracy gives you really efficient disciplined meeting structures, so that helps.

Traditional management hierarchies sometimes have a way of contributing to in-office sexism and other troubling interpersonal dynamics. Is this something you took into consideration when designing Holacracy?

It wasn’t conscious, but I do think it has an impact on that. One of the women that works at Zappos just wrote an article all about her experience there, and how this gives her even more ground to contribute than the typical management hierarchy. I’m glad she wrote it because I couldn’t have. As a male I could not have possibly written it with any degree of integrity, although I thought it made sense to me. I thought it probably had that effect, but she just called out her direct experience with it and it was great.

The management hierarchy was primarily developed in an era that was completely male dominant. So not knowing anything about why, you can probably assume that a culture that developed a way of structuring in an era that was completely male dominant probably developed structures that encoded that bias even if accidentally or unconsciously. Holacracy actually developed recently in a culture that’s much more egalitarian than the world was a hundred years ago. So it would stand to reason that anything that kind of emerged in the modern-day form is more likely to not have as much bias built in.

Holacracy integrates a lot of different energies. During the development of Holacracy it became a key kind of test for us: Does this system we’ve got embrace and integrate all these different energies, regardless of the different types and styles of people? Or, is it biased? If it’s biased towards more extroverted people, we have an issue. We’re not getting the best from everyone. Or vice versa. Whether it’s biased towards people that like quick, rapid decision-making, versus people that like more pulled back. Both of those have value. Each one has its place in the overall system. If you systemically bias against either, you’ve got a problem.

What we ended up with in Holacracy is that it does allow opposites, which is really interesting. Holacracy’s more structured than a management hierarchy, and it allows more freedom and more adaptability. And people often see those as at odds, which they are in most companies. You’re either a more bureaucratic structure or you have chaos and anarchy but freedom, right? And Holacracy is more of both. If you want really clear structure, and you want to know what’s expected of you, Holacracy gives you more of that than a management hierarchy.

But if you want more freedom, more autonomy, more ability to just adapt and to do whatever makes sense in the moment without structure getting in the way, Holacracy gives you more of that as well. This is one of the things that makes it really hard to convey. Because people are used to thinking of these things as opposed to each other. You either have structure or you have freedom. Holacracy lets you have freedom in structure and structure in freedom. It’s both at once.

What’s next for you?

Holacracy’s been exploding over the past year. We’re just trying to keep up. We’re trying to figure out how can we better support it. We recently open sourced the Holacracy method itself, the constitution, and the rules to the game. So we now have a much bigger community that’s helping to steward it and evolve it. That was a big move for us. It’s becoming a standard, if not the standard, in how to run a totally self-organized enterprise. We’re just trying to support it and keep up. I have no idea. I’m happy to follow where it leads.

First published at fastcompany.com.