Self-Deception

Self-Deception, Self- Delusion and Self-Denial

We had known Mary for many years before she unwittingly started us on a modelling project. Mary is a successful businesswoman with lots of energy and a huge heart. She is also seriously overweight. When we met Mary socially every few months she would enthusiastically tell us how she was on this or that new diet, and how she was losing weight and feeling good about herself. Strangely, over the years Mary never actually changed size. She might lose 20 pounds every now and then, but the next time we’d meet, she’d be losing it all over again.

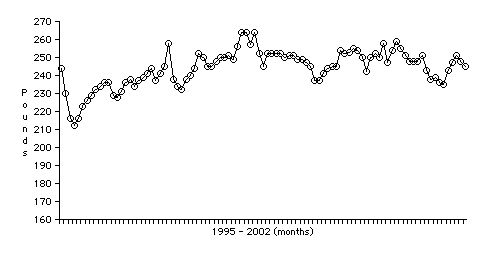

During one of our meals together we discovered an unusual thing about Mary. She told us that, regular as clockwork, she would weigh herself on the first day of every month. She recorded the weight on her computer and it would print out a graph which she proudly presented to us. The graph showed a line following the ups and downs of her weight over the previous seven years (see Figure 1). We studied the graph and it became clear that Mary’s weight had never risen above 265 pounds and (apart from a brief three-month period), had never fallen below 220 pounds. It had always fluctuated within a 45 pound band. Mary’s target weight was 160 pounds.

We didn’t see Mary for four months. When we did, she didn’t have the graph with her but it was obvious that the line had taken an upward turn. She told us how she was back on a diet that had worked for her years ago. She said how well it was going and how losing weight was much easier this time. Mary was losing weight again.

This got us thinking. How is it possible for a highly intelligent person to have ‘undeniable’ evidence that nothing is changing and yet not take effective action to do anything about it? How did she maintain the illusion that she was losing weight when all the evidence showed that thepattern of weight loss and gain stayed the same? How did she not notice that she was fooling herself year after year?

While thinking about Mary we realised that some of our clients had, in their own way, displayed exactly the same pattern of behaviour. One client failed to notice that he was not managing his finances effectively even when he went bankrupt for the second time. Another believed her husband would stop being violent despite years of evidence to the contrary. Yet another continued to maintain that he could be being a “social drinker”despite his alcohol-induced blackouts.

These clients repeatedly maintained: “I can manage money better”, “He might change” or “Social drinking is possible”. These are accurate statements: you can, he might, and it is possible — and they help to direct attention away from other facts which come with a much greater weight of evidence: you never have, he hasn’t in many years, and one or two glasses are never enough for you.

Clinging to such misleading beliefs when deep down one knows them to be untrue is what we call’self-deception, self-delusion and self-denial’ (self-DDD for short).

We group the various types of self-deception -delusion and -denial into one category because, although they may have surface differences, they have structural similarities. Also, since we are interested in modelling the organisation of patterns of individuals and groups, the label we give an experience is largely irrelevant. In our work, it is the client’s description of their experience that counts — and that will always have idiosyncratic elements. We use three terms and interchange them because we are not labelling a neatly defined condition — rather we are pointing to the general category of which each person will be a unique example.

When we researched the literature on self-DDD we felt that many traditional theories did not do justice to the whole pattern. So we set out to model our clients and, uncomfortably, our own patterns of self-DDD as well.

What is self-DDD?

When we deceive, delude or deny to our self, we mislead our self, we misrepresent or disown what we know to be true, we lie to our self, we refuse to acknowledge that which we know. InVital Lies, Simple Truths, Daniel Goleman notes that we do not see what it is that we do not see, because:

The mind can protect itself against anxiety by diminishing awareness. This mechanism produces a blind spot: a zone of blocked attention and self-deception. Such blind spots occur at each major level of behaviour from the psychological to the social. (p. 22)

Psychological blind spots create a not-knowing about something. However, in order for a system to recognise what to avoid, deny or mislead, it has to maintain knowledge of what to avoid — what it knows to be true. In other words, deceiving our self requires that we both know and not-know something. This apparent paradox is one of the keys to understanding how self-DDD operates.

The delightfully ambiguous title of Stanley Cohen’s book highlights that States of Denial are equally as evident with nations as with individuals:

People, organizations, governments or whole societies are presented with information that is too disturbing, threatening or anomalous to be fully absorbed or openly acknowledged. The information is therefore somehow repressed, disavowed, pushed aside or reinterpreted. Or else the information ‘registers’ well enough, but its implications — cognitive, emotional or moral — are evaded, neutralized or rationalized away. (p. 1)

Cohen goes on to explain how the ability to repress, disavow, push aside or reinterpret is often helpful, even necessary, in the development of our species and of civilisation. For example:

The inhabitants of Beirut, Bogota or Belfast cannot live in a permanent state of heightened awareness that a car bomb may go off at any minute. Some switching off is necessary to get through the round of everyday life. (p. 15)

Some people develop the capacity to switch off, turn a blind eye or fool themselves to such an extent that it limits their well-being and further growth. Like any natural pattern, self-DDD operates within the dynamic balance of a larger whole. Gregory Bateson was fond of saying, “There is always an optimal value beyond which anything is toxic.” (Goleman, p. 245). This is why an overdeveloped ability to self-DDD is a feature of many conditions such as anorexia, body dysmorphia, Munchhausen’s disease, physically abusive relationships, compulsions, self-harm and addiction.

In less dramatic ways self-DDD features in everyones’ life. Being able to deceive and delude ourselves is both natural and something that to some extent we all engage in. The following is a small sample of hundreds of commonly used metaphors and expressions that point to an apparently universal pattern of human behaviour:

I don’t want to know.

I couldn’t take in the news.

It’s got nothing to do with me.

Don’t make waves.

I looked the other way.

There’s nothing I can do about it.

I can’t believe this is happening to me.

Ignorance is bliss.

Let sleeping dogs lie.

Brush it under the carpet.

I’m just hoping it isn’t going to happen.

I’ll just pop in for a quick pint.

Why didn’t I listen to my intuition, again?

With a typical conflict or dilemma, we acknowledge both sides and that we don’t know how to resolve it — we do not deny there is a conflict.

While it is usual to think we self-DDD the unpleasant and troubling experiences of life, it is equally possible to deceive ourselves about pleasant experiences. This is often the case when there is an expectation that a pleasant experience will be followed by a painful one. A client said “it only takes me a millisecond to convert a compliment into a criticism.” When we enquired “And where does that ‘convert a compliment into a criticism’ come from?” she replied, “I can’t appear to be stuck up — that’s a no-no.” Accepting a compliment led to the gut-wrenching feeling of being “stuck up”. Better to deny any achievement in the first place and maintain the illusion of worthlessness.

The good news is: because of their paradoxical and contradictory nature, self-DDD patterns can be a doorway to the next level of personal development.

Levels

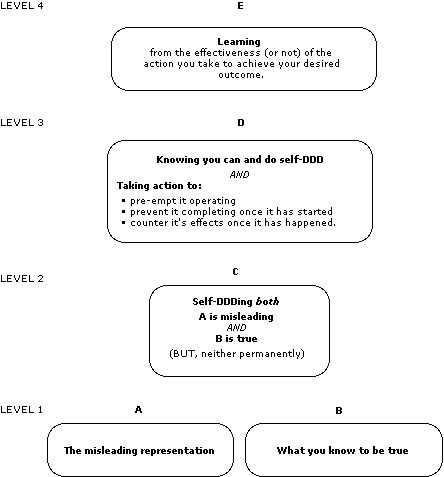

Below are two simple models which help explain how self-DDD operates at multiple levels and across multiple time frames. At the base of self-DDD are two contradictory representations or knowings. One is what we know to be true. The other is a misleading representation. At a higher, more complex level, we fool ourselves, temporarily, into thinking that ‘what we know to be true’ is not true and the misleading representation is true — a double delusion.

James’ example

For five years James filled in his income tax return without mentioning the rental income he was receiving from a lodger. He knew he should declare the income and yet somehow the figures never got onto the form. In conversation, James proudly proclaimed himself to be an honest man. He demonstrated this by being harsh on people he managed if he discovered them cheating on their business expense claims. When James did this he believed his own misleading representation. He really thought he was an honest man.

James’ system had to keep two truths from his awareness. The truth of his own cheating on the tax man and his own values, and the truth that saying he was an honest man was a lie.

Our modelling shows that people have to employ a variety of methods to successfully self-DDD — one is never enough. Some of the tricks James used were to not think about it, to not talk to anyone about it, and to ignore the possibility of being caught. He also managed to convince himself that:

It’s not important, it’s a drop in the ocean.

I’m honest everywhere else.

Everybody does it.

It’s too late to get the figures together this year.

I’d do it if it wasn’t so complicated to fill out the form.

The expenses will balance out the income anyway, so I’m saving the tax people time.

You will notice how James’ masterful reframes work together to create a web of believable statements. What’s more, declaring all those past tax evasions might have resulted in a hefty tax bill he could ill afford. It might even mean the possibility of prosecution and being exposed as a criminal. Over time the thought of living in accordance with what he knew to be true became associated with greater and greater negative consequences. This created a strong ‘away from’ motivation to “let sleeping dogs lie.” This, however, is only part of James’ story.

Feedback

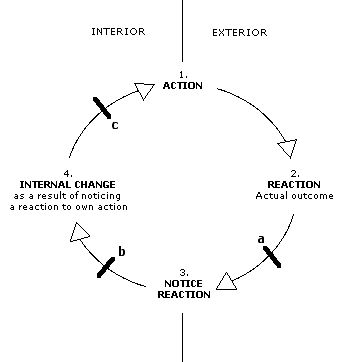

Figure 3 shows a simple feedback loop (see Developing Group notes, 4 June 2005). It illustrates that self-DDD can operate at three places in the cycle (marked by a, b and c).

| a. Literal Denial | “I fell down the stairs.” |

| b. Interpretative Denial | “He loves me really.” |

| c. Translatory Denial | “I’ll leave him next time.” |

Process a, between stages 2 and 3, keeps unwelcome information out of awareness. If you do not notice counterexamples or evidence that contradicts the misleading representation, you will never be called to question yourself. Stanley Cohen calls this literal denial and is usually quite obvious to an observer.

A physically abused woman says: “I fell down the stairs.”

More subtle and more common is Process b, between stages 3 and 4: interpretative denial. Here you find a way to justify, explain, diminish, reframe or otherwise discount the evidence. Natural selection plays its part because those interpretations which preserve the pretence are incorporated into the web of deception, and those that expose the pretence are discarded. Hence the system better learns how to maintain the status quo.

“He loves me really.”

Process c, between stages 4 and a new stage 1, is the trickiest to spot and the one that most often fools therapists, counsellors and coaches. Clients can be so sincere and so willing to make changes that we are misled by them misleading themselves. The longer the time lag between what the person says they are going to do and what they actually do, the harder it is to notice the pattern of deluding. It can take months and sometimes years of many apparent changes before it becomes clear that a higher-level pattern of remaining the same is operating. Following Ken Wilber, we call these unproductive translations.

“I’ll definitely leave him next time.”

The truth as James knew it kept surfacing in his awareness. Naturally this happened once a year during the completion of his tax form but it also happened spontaneously at other times. Something would trigger him to remember the tax evasion and be accompanied by a good dose of guilt. In these moments of self-reflection he would consider “coming clean” but would instead go through his whole repertoire of reframes until that unpleasant episode had faded. This gave him yet another good reason to not remember it in the future — to avoid the pain of guilt.

This is an important realisation. Self-DDD involves both in-the-moment processes which enable a person to act out of their misleading representation, and over-time processes which maintain the deception in the face of evidence to the contrary.

In Part 2 of this article we will see how James came to recognise his capacity to deceive himself and how he eventually learned to act from what he knew to be true (Level 4 in Figure 2).

A Systemic Perspective

Most models of self-DDD tend to restrict their description to the overt process of deceiving, deluding or denying. Rarely do these models account for the longer-term replicative nature of the pattern, or put it in a developmental context.

We start from the premise that self-DDD has evolutionary adaptive value and in many situations is necessary for healthy functioning. Viewed systemically, self-DDD behaviour is an emergent property of the configuration of the system.

To self-DDD, that which is denied must also be maintained. This is for two reasons: (i) if we were to completely forget, delete or distort the original knowing, we would no longer need to deceive our self (a person who tells a falsehood but who believes it to be true is not lying); and (ii) we need to maintain a knowledge of what has to be denied in order to know what not to say and do.

Plus, to successfully self-DDD we have to maintain the delusion in the face of contradictory evidence and feedback that accumulates over time. This requires the system to learn a variety of ways to detect and neutralise potential threats which would reveal the self-DDDing process. This process, however, cannot cope with every eventuality. Now and then inconsistencies and doubts surface in awareness. The result is an inner conflict and cognitive dissonance, which is itself highly unpleasant and therefore subject to more self-DDD. Eventually we learn to live what Jean Baudrillard calls a “simulation” of the truth.

Using an organic metaphor, the self-DDD process takes on a life of its own, and self-preservation becomes its purpose for existence. The components continually remake the whole of which they are a part, which in turn provides an environment for them to exist. Just as cells and the organism are in a symbiotic relationship — each depends upon the other for their continued existence — each element of the self-DDD process is held in place by its interconnections within the web of deception.

Having previously modelled the structure of self-sustaining double binds (further described in our book, Metaphors in Mind), we soon realised that self-DDD is inherently a double-binding pattern. Even when the deceiving process is noticed or pointed out, its very nature is to negate that information. Furthermore, to break out of this cycle we not only have to start living in accordance with what we know to be true, we have to admit to ourselves and others that we deceived. And, the longer we deceive, usually the harder it is to admit it. Hence the way out of self-deception is itself bound.

From this perspective, a person is not bad, resistant or weak-willed; they are doubly bound by their own patterns of thinking and feeling. They are in a self-created maze within which all exits appear to be sealed.

But, and it is a very big BUT, we cannot maintain the pretence of the simulation all the time. The configuration of self-DDD contains the seeds of its own transformation. By preserving what we know to be true we always have the potential to fully acknowledge what we have denied and to accept our capacity to deceive ourselves. As long as we recognise that we can fool ourselves, and take steps to counter this tendency, we can continue to live in accordance with a higher-level truth.

Ethical Questions

Since we anticipate this topic will be of interest to many therapists, counsellors, coaches or other facilitators of change, we want to finish Part 1 with some ethical considerations.

R. D. Laing recognised in Knots (p.5), the danger of one person deciding another person is self-deceiving, deluding or denying:

He does not think there is anything the matter with him

becauseone of the things that is

the matter with him

is that he does not think that there is anything

the matter with himtherefore

we have to help him realise that,

the fact that he does not think there is anything

the matter with him

is one of the things that is

the matter with him.

Given that at best people are only dimly aware that they are deceiving themselves, a number of questions arise:

- How would you know a person was self-DDDing?

- When is it in the best interest of the self-deceiver to be informed?

- When should the ‘wider system’ be informed, even if this conflicts with the interest of the individual?

- How do you take into account the deceiving nature of the self-DDD pattern?

- And how can this be done ‘cleanly’ (i.e. without imposing your ‘map of reality’ on them)?

And, it is worth remembering that if a person doesn’t act from what they know to be true, andthey know truthfully that they could have (i.e. they have evidence for this belief) — then it’s a choice and not self-DDD.

Finally, becoming aware of your own self-DDD patterns and how these can be transformed into self-truthfulness is a great way to develop the modelling skills required to work effectively with others who self-DDD. This is the subject of Part 2 of this article.

|

You can download a 1 hour 45 minute audio recording of a conference presentation we gave on this subject (including a live demonstration of taking a participant through a self-DDD activity) from:

www.cleanchange.co.uk/cleanlanguage/shop/self-deception-self-delusion-and-self-denial/ |

<a “=”” name=”footnote1″>NOTE 1 This feedback loop model can be mapped on to the Kolb ‘Learning Cycle’.

References (and including part 2 too)

Baudrillard, Jean, Simulacra and Simulation (University of Michigan, 1994)

Cialdini, Robert B. Influence: Science and Practice (Harper Collins, 1993) – especially pages 94 – 133.

Cohen, Stanley, States of Denial: knowing about atrocities and suffering (Polity, 2001)

Collins, Jim, Good to Great (Random House, 2006)

Covey, Stephen, The 7 Habits of Highly Successful People (Free Press, 1990)

Fritz, Robert , The Path of Least Resistance (Stillpoint, 1986)

Goleman, Daniel, Vital Lies, Simple Truths (Bloomsbury, 1998)

Kline, Nancy, Time to Think: Listening to Ignite the Human Mind (Cassell, 1999)

Laing, R. D., Knots (Penguin, 1992)

Lawley, James & Tompkins, Penny, Metaphors in Mind: Transformation through Symbolic Modelling (Developing Co, 2000)

Peck, M Scott , People of The Lie: The Hope for Healing Human Evil (Arrow, 1983)

Prochaska, James O. , John C. Norcross & Carlo C. DiClemente, Changing for Good(Quill 2002)

Ramachandran, V S & Sandra Blakeslee, Phantoms in the Brain (Fourth Estate, 1999) – especially chapter 7.

Senge, Peter, The Fifth Discipline, Doubleday, 1990.

Wilber, Ken, Sex, Ecology, Spirituality (Shambhala, 1995)

1 Comment